The Old Ash Tree and the Reverend John Ashburnham (1839)

Ash trees were not common in Pevensey, but early in the nineteenth century there was a fine ancient specimen in the churchyard of St Nicolas. In November 1839, the vicar decided to cut it down.

The churchwardens disagreed with this decision, and enlisted the support of the rural Dean. Despite this opposition, the vicar wished to go ahead, and called in a team from Hailsham: a wheelwright and a carpenter turned up, along with a timber tug and several helpers. When the workmen reached the church gate, they found a churchwarden, Alfred Plumley, barring their entrance.

Undeterred, the workmen hopped over the church wall and set about felling the tree. The local residents heard what was happening and ran to defend the ash, taking the tools away from the workmen. The local constable appeared, siding with the churchwarden and the crowd. The workmen appealed to the curate, the Rev. Julius Nouaille, who scurried about, taking down the names of the rebellious locals. The tree was not felled that day, and the vicar later said he would let the matter drop.

It is an entertaining picture of local life in 1839, but there is an unhappy background. On November 29th 1838 there had been a great gale all along the south coast, and the church building was damaged. There was a vestry meeting to assess the damage to the church. In Plumley’s version, the vicar said that he was exempt from parish rates; but he kindly offered to contribute £5, which he did not subsequently pay. During this meeting a proposal was made to raise the money by selling the great ash tree. This was rejected immediately, but perhaps the idea had lodged in the vicar’s mind. He wrote to the curate later, instructing him to have the tree felled. The churchwarden got to hear of it and called in aid from the ecclesiastical authorities, hence the confrontation in the churchyard.

The vicar was later insistent that the tree was being removed for safety reasons: also, one of the churchwardens had been sub-letting the vicarage, and an atmosphere of violence was building in the village. He also denied ever the offering five pounds.

The vicar – the Reverend John Ashburnham (1770 – 1854) – could have afforded the five pounds. He was the son of Sir William Ashburnham of Guestling. The family had been in Sussex for centuries and was related to the nearby Ashburnhams of Ashburnham Place. (Strangely enough, the Ashburnham coat of arms includes an ash tree.)

.jpg)

John Ashburnham studied divinity at Cambridge and entered the Church. It was helpful that his grandfather was the Lord Bishop of Chichester: In 1796 the Lord Bishop appointed his grandson as Prebendary and Chancellor of the cathedral.

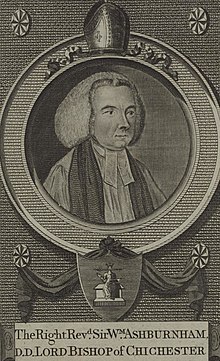

We do not have a picture of John Ashburnham, although there is an engraving of his grandfather, the Bishop (left).

In 1816 John Ashburnham, as Chancellor of the Cathedral, had to appoint a suitable vicar for the very lucrative parish of Pevensey. He decided to appoint himself.

As vicar he received just under £1,200 a year and, in return for this, he did nothing. The religious affairs of the parish were left to a curate, who might typically expect an annual income of £50. John Ashburnham also acquired the living at Guestling, worth £400 a year. Adding in the proceeds from his roles in the cathedral, he had an annual income of about £2,500 per annum (when an agricultural labourer earned £25 p.a.) *

In his first twenty years as vicar, John Ashburnham was said to have conducted just one service. This was probably not true as – in order to become established as vicar – he conducted both morning and evening prayers on 17th March 1816. After that he was absent, and the local church properties were allowed to rot. The parsonage was so decayed that it was being used to house paupers from a neighbouring parish.

The vicar’s income came from tithes – a tax of ten percent on the local farmers’ earning. In February 1833, there had been a meeting at Pevensey’s New Inn, chaired by the mayor John Whiteman. The meeting opposed tithes and sent a petition to Parliament. There was a specific problem for Pevensey, in that the tithes on grazing land were especially onerous to compute, and any mistake could be expensive. The vicar refused to consider an easier method. Added to this was the galling fact that the vicar took no part in the religious life of the parish.

John Ashburnham lived on until 1854, eventually inheriting his father’s baronetcy. When he died the still-lucrative post in Pevensey went to Henry Browne, a biblical and classical scholar, an authority on Greek and Hebrew, and author of many works on biblical chronology. Browne was active in Pevensey, and even became a Freeman of the Corporation.

* £1 in 1830 was worth approx. £110 today, so the vicar’s annual income would be worth in the region of three hundred thousand pounds.

More details can be found at:

Brighton Guardian - Wednesday 06 February 1833

Hampshire Chronicle - Monday 12 February 1816

Sun (London) - Friday 06 December 1839

Constitution of Chichester Cathedral By Mackenzie Edward Charles Walcott

The Keep ESRO, Ashburnham letters