Lily Woolven, the Insubordinate Schoolmistress of Hankham

In the 1890s, it was not easy to recruit schoolteachers to the isolated hamlet of Hankham. The local headmaster Mr Boyles must have been pleased, in the summer of 1898, to appoint Miss Lily Woolven as Assistant Mistress. She was not a qualified teacher: in the jargon of the time she was an “Article 68”. This meant that Lily was female and over eighteen, had a presentable appearance and had been vaccinated. Provided that the schools Inspector raised no objection, she was permitted to teach children. The local ratepayers were keen to control costs, so unqualified teachers were welcome.

Lily began in July, working alongside another young woman, Mary Ward. Mary had been at the school for two years, and was very popular among the parents. Lily, however, got off to a bad start. She ‘would persist in knocking the children about’. She was accused of hitting children round the head with books. There were complaints from many local parents including some whose names are still found in Pevensey today: Funnell, Miller and Elphick. A Mrs Turner complained that her son was up all night after being beaten around the head. Mr Boyles asked her not to pursue the complaint as he did not wish to harm Lily’s career. Mr Boyles asked Lily to stop hitting the children and, according to her, she did stop.

We don’t know very much about Lily Woolven. She had a sister called Phoebe, who married a Mr Goble of Lydd. It was said that LIly had a bad temper. We are also told that she was a good-looking young woman: ‘lively and attractive’ according to a local paper.

The headmaster encouraged her to qualify as a teacher, and found her a pupil ready to pay for private music tuition: the tuition would be in his house using his pianoforte. Lodgings were expensive, so Mr Boyles invited Lily to stay in a bedroom in the schoolhouse, at a much-reduced rate. Lily preferred to share lodgings with Mary Ward. This meant that she was short of money, and she had no parents to help her. Mr Boyles very kindly offered her two shillings a week out of his own modest salary. Quite what Mrs Boyles made of all this is not known, but Mr Boyles seemed very happy with his new Assistant Mistress.

Then one evening in the autumn of 1898, Mr Boyles saw something which left him well and truly triggered. He caught sight of Lily and Mary on the road in Hankham, talking to a young man.

He soon complained to the school Managers – Mr Gardner and Major Stillwell - who interviewed Lily. By her account, they were concerned with the young man. In their account, they were mainly interested in Lilly hitting the children. The two Managers leaned on Lily, who wrote a letter of resignation. Soon after, though, she had second thoughts: she wrote to the members of the Board, complaining of unfair treatment.

This was all discussed at a meeting of the Westham School Board in November 1898. It was a very well-attended meeting, and the Chairman threatened to clear the hall when the public became too vocal in Lily’s support. Lily insisted that she and Mary had met the young man a few times. Mr Boyles had insisted that they were disgracing the school by chasing after a strange man, night after night.

The Board noted that the women were perfectly at liberty to talk to anyone they wished in their spare time. And Mr Boyles had difficulty explaining the timing of his complaint. Lily had clearly been hitting children in July, but the headmaster had not informed the Managers then; there had been no complaints from parents since then. Mr Boyles knew all about the hitting while he was being so helpful in the matter of lodgings and money; more importantly he knew about it when he offered his help to obtain a pay raise for her. Only when he saw her with the young man in October did Mr Boyles start to complain.

The Chairman – Mr Gardner – agreed early on that he and his fellow-Manager Major Stillwell had gone beyond their powers when they interviewed Lily. Even so, he supported Mr Boyles. But Lily had the backing of many on the Board, including a powerful local figure, the brickmaker Jesse Dann. He called the whole matter a ‘a paltry trumped-up affair’ which could injure ‘a young, tender woman’. Another Board member, Mr Spice, suggested that Miss Woolven be given an increase in salary.

The local paper described her sitting in the court, ‘an attractive young lady . . . armed with a pencil and notebook.’ Obviously, there was some suspicion that Mr Boyles had himself noticed these physical charms. The public took Lily’s side and the press described the Assistant Mistress as ‘so heroic and English’.At the end it was agreed that Miss Woolven would have to go at some point, but the board would assist in finding her a new position. Mr Boyles was judged to have been indiscreet.

He was not going to let this go. In February 1899 the Board was again in turmoil over the affair. There had been another letter from Lily Woolven. Mr Boyles had written a critical and possibly inaccurate entry in the school log book, and this had been seen by an Inspector. One Board member, Mr Thornton, said that the whole staff should resign. He expressed his own dim view of the headmaster, repeatedly using such strong language that the Chairman had to end the meeting abruptly.

In March 1899 the matter surfaced yet again. A clergyman from Hailsham had been considering employing Miss Woolven and had been shown the log book. Jesse Dann was very concerned that the log-book might allow the headmaster to ‘vent his spleen’. Miss Woolven was still on the school staff: she was obviously made of stern stuff. Jesse Dann wanted her to resign but did not want her to go without finding another position. Major Stillwell, Manager of the school, said Lily was ‘kicking against authority’ and that her letter was ‘another act of insubordination’.

It seems as though Lily had found another position in Hailsham, working under a female teacher. The Board promised to give her a testimonial, and the wording is beautifully contrived:

“I can recommend her as a very energetic teacher, and, as far as I have seen, has taken great pains in instructing the children.’

At this point, alas, Lily disappears from the record.

Endnote: she does not really disappear. Lily Woollven (the spelling varies) married John Henry Lambert, a house decorator in 1901 and had a daughter called Enid. Her sister Phoebe began to drive motor cars in 1920.

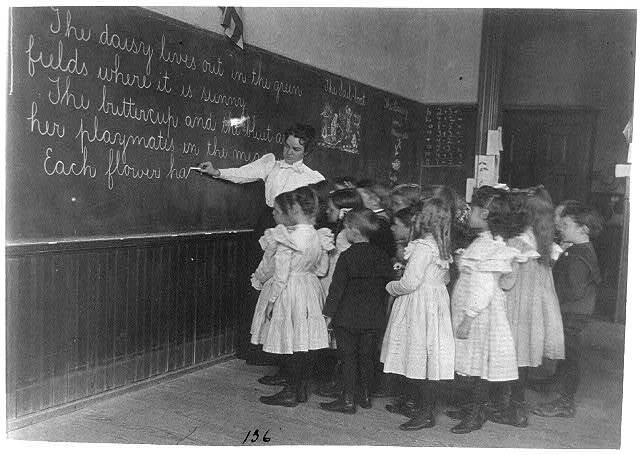

Old Time Education: The picture is from the Library of Congress and sadly does not represent Lily

Sources

Bexhill-on-Sea Observer 19th November 1989, 11th February 1899, 8th April 1899

Sussex Agricultural Express 19m November, 1898, 11 March 1899