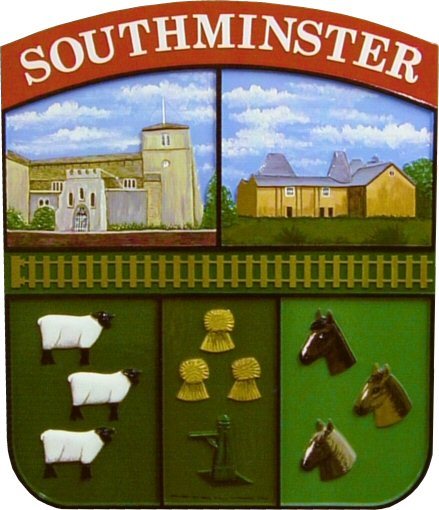

Southminster grew from Iron Age and Roman buildings and Saxon settlements of the fifth century. “Minster” suggests that Southminster had the chief church of the Southern Dengie Hundred during Saxon times. Parish churches only began to develop in the 11th Century. “Hundreds” were administrative areas defined differently in different places. They could refer to population, to men under arms, to the tax system, or to an area of around 12,000 acres. The “Dengie” Hundred took its name from its inhabitants: “Woodland people”. In time, the forest was cleared and saltings reclaimed as pasture. Until the Industrial Revolution, Southminster was a major producer of sheep for wool. Sheep stations were called “Wicks”. The name continues in several local farms.

During the Middle Ages, the Crown, the Bishop of London and the Priory of St Osyth between them owned the village and took its rents until the Priory closed in 1540. Thomas Sutton bought the village in 1585. He gave its rents to his charity, Charterhouse, in the City of London. Charterhouse still appoints the Vicar. In 1832, Charterhouse Governors established the Parish Pump at the corner of Goldsands Road as a public, clean, water supply.

For most of the last eight hundred years, from 1218 to 1937, Southminster was the Dengie Hundred’s market town. For most of the next five centuries it was the Hundred’s “capital”. In the nineteenth century it had an important horse market supplying London’s needs. The Magistrates’ Court and Police Station arrived in 1901. Southminster is still the local police headquarters, but the Court has moved to Witham, the building is now the Library.

The chief public building is the Church of St Leonard. It was expanded to its present size by Abbot John Vyntoner of St. Osyth (1533 – 1537) and Alexander Scott, (Vicar 1803 – 1840). William Lowder (Vicar 1891 – 1901) added the Screen, chancel stairs and High Altar.

Southminster provided men in most wars from Saxon times onwards. During the First World War, at least sixty men of the village died in action: nearly five percent of the male population. The Memorial Hall and the obelisk in the churchyard remember them. During the Second World War, Southminster was in the path of enemy bombers attacking London. A bomb destroyed much of the village centre and damaged the Parish Church.

Southminster’s prosperity has varied. Famine recurred during the Middle Ages. Farming prospered during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, the profits from the Essex wool industry moved north as machines in Yorkshire replaced local hand weaving. Repealing the Corn Laws in 1846 gave cheaper food for the towns but hurt local farmers.

Formal education came to Southminster with the foundation of two Church Schools in 1814 (boys) and 1815 (girls). Southminster Primary School is now a well-equipped, well-organised establishment with an excellent, wooded site and its own indoor swimming pool open to the public.

Railway goods services began in 1957. When a nuclear power station was sited at Bradwell, Southminster station was the railhead for construction materials. Later, flasks of used fuel left for Sellafield by rail. As a consequence of building and continuing operations for the power station, Southminster’s population doubled. Between 1962 and 2002 the power station employed many Southminster people previously living precariously as market gardeners and farm workers. The power station also helped Southminster’s railway to escape the Beeching axe.

Rail Passenger services, started in July 1889, enabled commuting to London to grow during the twentieth Century. Southminster continues to grow and develop as a dormitory town for London, Southend, Basildon and Chelmsford. Growth increased further after 1986, when electrification enabled direct trains to London. Southminster’s population trebled between 1952 and 2001 largely due to the power station's residential needs

Southminster today is an important travel, trading and eating hub in a rural area. Nearby are some of Britain’s most important coastal wetlands. Three Sites of Special Scientific Interest lie within the village. A conservation belt protects the coast. It’s a good place.

Councillor Ken Dunstan