Melsom’s musings

An occasional series which might provoke comments. I’m setting out to try and articulate some of the chess knowledge I’ve acquired over the years in the hope that it might be helpful to others or at least challenge why we do what we do. Some of it will sound familiar, chess has been around a long time and I’ve learnt over the years from many diverse sources not specifically acknowledged. And these are my personal thoughts, and should be treated with suitable caution. In this first article I’m going to start with some thoughts about the start of the chess game, something I expect to return to at a later date.

The Opening

The opening phase of the game is the first dozen moves or so in which you and your opponent seek to put pieces on good squares that will help in your plan to gain superiority later in the game. If you put your pieces on good squares at the start of the game, then they will work better together later on. A single piece on a bad square may prove your downfall if you have to waste time putting it on a better square later, or maybe the game might pass that piece by completely if it is somewhere with no influence on the developing struggle, so you need to ‘know’ your openings.

[Please note: People do often mistakenly talk as above about ‘knowing an opening’ – I know the Dragon, or I’ve been taught the Benko (chess has lots of names for sequences of moves  ) Although it is important to understand move sequences – as in some openings you can go wrong very quickly if you get the precise order wrong- it is more important that you understand the general aims and strategies that might arise. And you need to understand what your opponent wants to achieve (what is a good result of the opening for him) as well as what you are trying to do, so that when something unexpected happens, you can distinguish between something which is unusual (you won’t have seen everything) and what is bad (because they understand less than you.) And then you can respond appropriately…] Understanding the aims of both sides is a challenge, but very necessary as you don’t get to play all the moves. Key point for juniors – your opponent gets to play moves as well which may challenge your plans.

) Although it is important to understand move sequences – as in some openings you can go wrong very quickly if you get the precise order wrong- it is more important that you understand the general aims and strategies that might arise. And you need to understand what your opponent wants to achieve (what is a good result of the opening for him) as well as what you are trying to do, so that when something unexpected happens, you can distinguish between something which is unusual (you won’t have seen everything) and what is bad (because they understand less than you.) And then you can respond appropriately…] Understanding the aims of both sides is a challenge, but very necessary as you don’t get to play all the moves. Key point for juniors – your opponent gets to play moves as well which may challenge your plans.

So what openings should I play?

As with all aspects of chess, developing an understanding of openings takes time, and many people continue to have relatively limited knowledge even after many years of playing. Some change their openings frequently rather than try to obtain a deep understanding of any one system. Sometimes this is for variety, or because they simply don’t like the positions that arise. They may feel the position is too tactical or too passive. But constantly re-inventing yourself with limited time to spend on chess may be harmful, unless you can get to a level of deeper understanding with your new opening.

Personal Style

What sort of positions do I like? Do I like to launch a direct attack on the king? Am I happy playing more slowly against weaknesses in my opponents position. Am I happy in blocked positions? Do I like defending and waiting to counterattack? Whilst there are plenty of openings that offer a mixture of quiet and aggressive options, others rapidly become very complicated and tactical. You won’t see me play the Sicilian as Black, but some club members enjoy the tactical melee that can frequently result. And I have a poor grasp of fianchetto systems (putting a bishop on g7 or b7) so the Pirc and the King’s or Queens Indian are not normally for me. (I’ve been known to play some stuff just for variety when faced with a less proficient opponent. This is not to be recommended, as it is all too easy to wander into the unknown and get confused.)

Time saving

Many chess players soon realise that even the opening phase of the game is complex. Some choose to play openings which are relatively uncommon, so that both players are left to their own devices. Some of these are good, others relieve much of the tension at an early stage. I played 1 b3 for a number of years because I realised that there were too many replies to e4 that I didn’t have time to analyse. And I still play 2 c3 if my opponent answers 1 e4 with...c5. Others will try to play universal systems where you can quickly bash out half a dozen moves almost without thinking about what your opponent is doing. But you still need to understand the opening ideas!

Other factors

The opening is rarely decisive in chess at lower levels where it is possible to make more inaccuracies and not be punished. But some openings may be less effective against stronger players and may place a greater requirement on you to really understand your stuff.

Some juniors are taught to play gambits and other tricky lines, so that they can think about fast piece development and tactical ideas. These are good lessons, but winning lots of games in these openings may not be a pointer to success further on. The Italian Game with e4 e5 followed by bishops and knights contesting the middle of the board is adequate and can be seen even today at the highest levels of chess but I have seen plenty of players who can play six moves and then get stuck. Key ideas need to be learnt as well as moves. (I might have said that before  )

)

Your knowledge may never be put to the test. I used to know a lot about the Benko Gambit, but many of my opponents played moves that meant it never occurred on the board. I knew less about the systems they played. So you want to use your time learning about positions that are likely to arise at your level of the game.

Why I don’t recommend the French Exchange variation or other methods of simplification

(e4 e6, d4 d5, ed5 ed5)

White starts with the advantage of the first move, and should be seeking to set the agenda. Chess is about psychology as well as good moves - the stronger player will normally win irrespective of approach, but if my opponent simplifies the position to dodge my pet lines I can start to relax. He may of course be an expert in these lines so there may be a degree of bluffing but normally he is just trying to keep things simple. Chess is a game played in the head so I’m not keen on moves that just duck the challenge, unless they are in some way intended to create tension or imbalance. Symmetrical positions can be tricky, but not that much, so avoid them.

I’ve deliberately not set out to tell you how to play openings, but a search on the internet for ‘chess openings’ will quickly lead you to a variety of articles and also some basic principles of opening play. Having whetted your appetite I’ll cover some of this stuff next time.

Cautionary note: There are an awful lot of books out there on individual openings and a lot of them are too detailed for most people or cover too narrow a subject matter. Do ask other players for recommendations and try to see a book before purchasing. Some of the publishers also now allow you to download sample chapters from books in pdf form, so that you can see the level of detail. [ I’ve mentioned books as the most common or traditional learning tool, but there are also videos on line or DVDs] I’ve recently purchased two rather large volumes which provide a repertoire for black after e4 e5 and a third more concise book on d4. I like chess books, although don’t always read them as thoroughly as I should. But even with these purchases I have to work out what I want to play going forward as white!

The author would welcome feedback or questions from club members or visitors, perhaps sharing experience on learning openings/ constructing an opening repertoire, good learning resources for all levels. Indeed any reaction at all would be good.

Mistakes in chess

It is summer, a time when most of us put away the chess pieces and pursue other activities. Summer also provides a chance for reflection on the season past, and perhaps some consideration of where our games went wrong. This new series which I hope will grow over the summer looks at mistakes and the reasons for them. For however much effort we put into our chess many games just come down to a single error costing decisive material from which recovery is unlikely. There are many reasons for these mistakes, ignorance, rushing, miscalculation, fatigue, playing on general principles and not respecting the specific details of the position. Mistakes can arise in the opening, as we transfer into the middlegame and start to think increasingly independently and during the end-game where even with fewer pieces the need for accuracy is still there. If you think of king and pawn endings, there are no big pieces on the board but plenty of care needed. If we can eliminate the simple mistakes, we can make a significant leap forward in our play. Though we won’t be error free, simply that our mistakes will be of a different order.

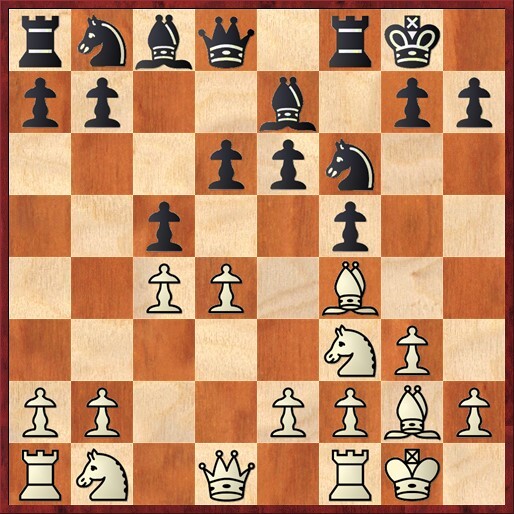

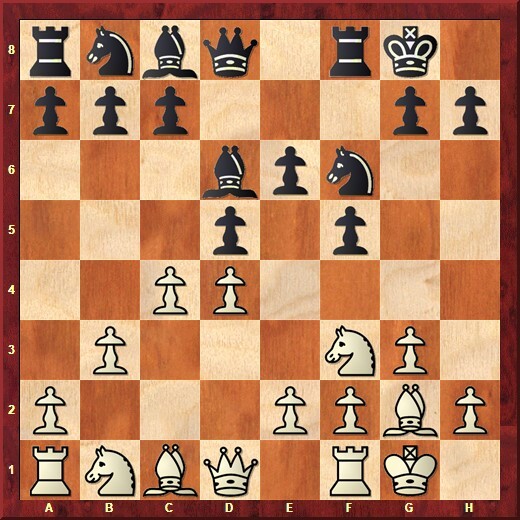

Here White has managed to achieve a sound opening position, but perhaps unsure how to proceed, replying to Black’s push of his pawn to c5, plays the N to c3. What has been over-looked?

Well Black’s push of the c pawn attacked its rival on d4. The d4 pawn is defended twice but either re-capture will allow black to play e5, hitting the higher value piece on d4 and on f4. No real option but to go a pawn down.

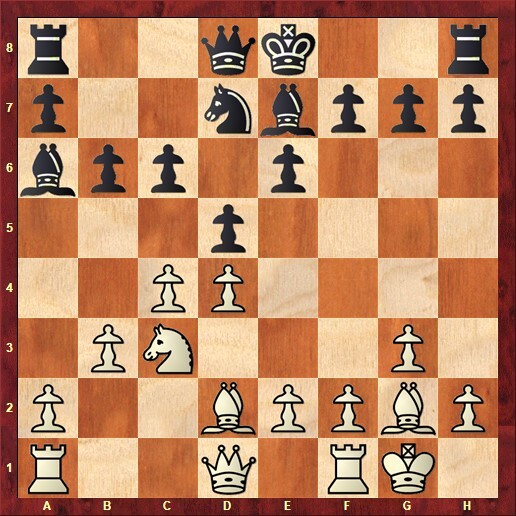

In a subsequent game, with the same young person playing white, something similar happened.

It took me a while to work out why this mistake might have arisen, as there is a lot going on in the position immediately prior to the mistake. The position is barely out of the opening phase, and there is some early tension to consider with the d5 pawn and the pawn on c4. In this position black plays his rook to c8. This renews the attack on c4 because the Bishop on g2 can no longer capture the c6 pawn. White plays an indifferent developing move Qc2 and loses a pawn.

It is not uncommon for players to play early moves with confidence and then flounder, as there is a clear difference between playing by rote and playing with understanding. It is necessary in chess to exercise a degree of caution, especially when outside your comfort zone. And it is essential to evaluate every position on its merits – the black rook move clearly changed a key aspect of the position.

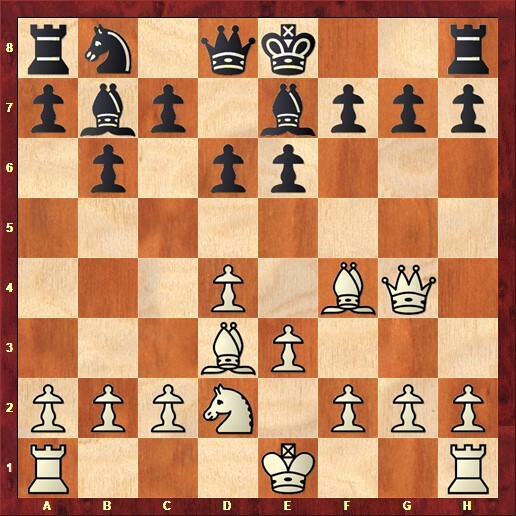

And to show even strong players make mistakes my final example for now;

It is an early morning game in June 2018 between two Grandmasters. White has just played the attacking move Q-g4, asking black a question or two about where he intends to put his king, and what to do about the g7 pawn. The move also defends the white pawn on g2, which had previously been offered as a temporary sacrifice since lines after Bxg2 and Rg1 hitting the g7 pawn were probably better for white. White’s plan is not unusual, but he has forgotten something. Black can counter-attack to decisive effect with pawn to g5! A handful more moves were played but g5 followed by h5 and h4 just wins. White seems to have overlooked the lack of space for his pieces. Big mistakes in top level games happen more often than you would suppose, and for similar reasons to those mistakes of mere chess mortals, rushing, fatigue, moving on auto-pilot. However, familiar you think the position is, each position needs to be considered on its own merits.

More blunders

Every week there are hundreds often thousands of games being played around the world and transmitted live or otherwise recorded for posterity. These provide rich pickings for examples of instructive mistakes. My writings here are not unique and some people have even written whole books around early and common mistakes in various openings.

For those with an inquiring mind who would like to do this themselves, the simplest starting point is to select a large batch of games, and then sort by game length and decisive result (for example, all wins in under 20 moves). If your database software is sophisticated enough you might also sort by opening, so that you learn to recognise common traps and tactics that arise in positions you play. And playing through games in your opening systems is also a pretty handy way to gain familiarity with the positions that arise even without the blunders that we cover here. Those with less time can obviously just follow me and other writers. Please note one word of caution. Even reputable sources for games such as TWIC have scores that are incomplete or have the wrong result. If the live feed breaks down, not every organisation will manually transcribe the remaining moves, so the correct result might be recorded but it may have been many moves later. A recent example of this was the European Club event where all games were on live boards, but the TWIC capture of many of the games is just the opening phase.

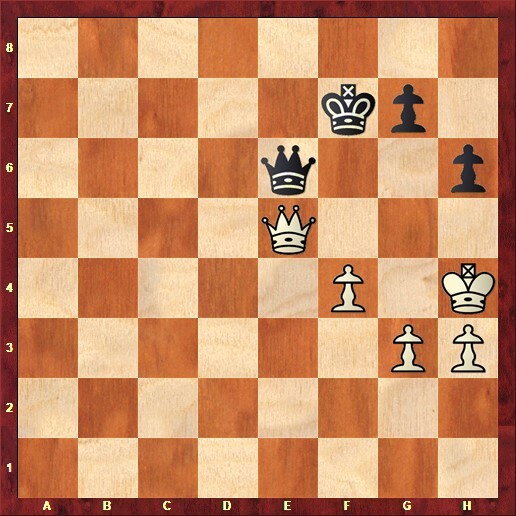

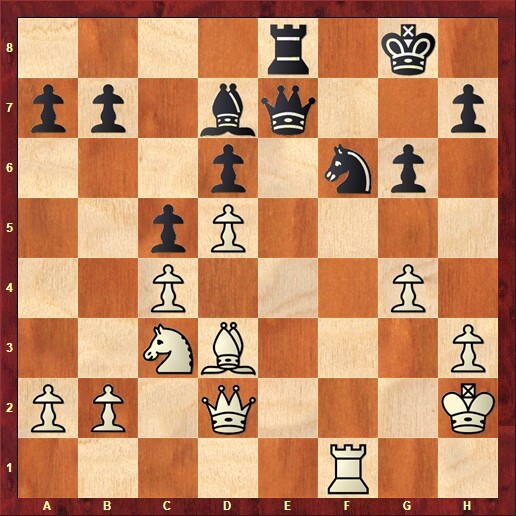

This first example is not from opening play, but from the very end of the game. White has been pressing in an end-game a pawn up. End-games with queens and pawns are notoriously difficult because it is hard to avoid constant checks on your king from the opposing queen. The player with the extra pawn is hoping that s/ he can force the exchange of queens and go into a winning endgame with an extra pawn. GM Fodor playing the top seed Adams at the British Championship found his own personal Hell in Hull.

White has just played the queen from c3 to e5, when he is suddenly hit by pawn g5. â¹ Hard to explain although at a less exalted level I’ve walked into these sorts of traps in rook and pawn endings. Our desire to convert our advantage can cause a disregard for the safety of our own king!

From Hull to Copenhagen. In many parts of the world tournaments are run in a single section from grandmaster to keen amateur, and you can be paired against very strong players for a number of rounds until you find your level ( sometimes if in the wrong place in the seedings, you can go from beatable opponents to really strong players for a whole event] So how to cope? Well not like this, but at least Black got to enjoy Copenhagen. [ It is of course entirely possible that the Danish player concerned had spent part of the day at work before the game, and he was just rushing to get home rather than see the sights! Not uncommon when rushing to do silly things.]

A standard position has arisen in the Dutch. One might expect black to counter the threat of pawn to c5 by putting a pawn on b6 or c6. Instead he played Qe7 and the bishop has nowhere to go â¹ This mistake would have been avoided by basic consideration of what white was threatening, so rushing seems a good explanation, albeit that the player’s determination/concentration might have been influenced by playing somebody really good.

And back for now to the British – a moment from a subsidiary event. A tense and un-balanced position. White has an edge but needs to be wary of Black counter-play, because of the holes around the king. Qg5 brought a premature end when Black replied N x g4. There were warning signs here, the queen went to a square where it was undefended and attacked the black knight (the winner subsequently told me he half expected this blunder to occur).

I did promise some examples of my own blunders and had hoped to publish more frequently. These will have to wait another day as our current site no longer supports game replay. However, if anybody else spots an instructive blunder anywhere, please contact me and we will see if we can pop it up here.