On this day in Wembury — 12 August 1885

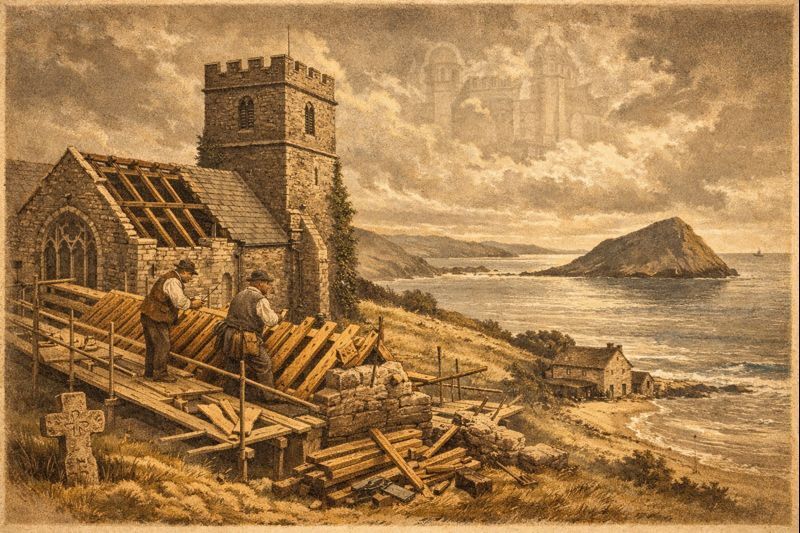

The Western Morning News devoted a long and vivid article to “Wembury and Its Church”, describing both the historic beauty and the ongoing restoration of St Werburgh’s, funded through the generosity of Mr Cory of Langdon Court. The piece began by painting a striking picture of the church “standing on a bold cliff opposite the Mewstone, on the eastern side of the entrance to Plymouth Sound.”

The population of Wembury village lay nearly a mile inland, and only the old mill on the beach below shared the church’s solitude. The paper noted how this remote situation was shared by other coastal sanctuaries such as Revelstoke, now in ruins, and Rame Church across the Sound. These ancient buildings, it suggested, had been placed almost as beacons for mariners rather than as churches for the local people, perhaps on the sites of even older pagan temples, whose worshippers made sacrifices by fire and libation before Christianity came to West Britain.

The writer lingered on Wembury’s “mystic associations with the well-nigh forgotten past,” recalling the battle fought there in 851 between the Devonshire men led by Ceorle and an invading army of pagan Danes. The Devon men won after great carnage, and some had supposed that the first church was built to commemorate that victory. The article judged it more likely, however, that the site’s religious use was even older.

It observed that Wembury Church was unusually dedicated to a Saxon saint, St Werburgh, “the holy daughter of that pagan Wulfhere, King of Mercia, who after he had conquered the West Saxons was converted to Christianity and turned the pagan temples into Christian churches.” St Werburgh was described as a nun of exceptional piety who ruled several monasteries in Mercia. After her death about the year 690 her body was laid in a costly shrine at Hanbury, later moved to Chester, where her relics were destroyed during the reign of Henry VIII. Her shrine, which had been decorated with images of the kings of Mercia and her royal ancestors, was converted into the episcopal throne of Chester Cathedral.

Quoting the monk John Bradshaw’s Life of St Werburgh printed in 1521, the article gave lines describing her as “chief protectress of the said monastery” and “special primate and principal president there ruling under our Lord omnipotent.” It reflected that in a time when many modern churches were being built close to their congregations, it was remarkable that the people of Wembury still made the journey to this “distant and isolated church of their fathers.” Mr Cory, it said, had wisely chosen to restore the old building with all its historical and archaeological interest, rather than build a new one nearer to the village.

The church’s main structure—its nave, chancel, aisles, and tower—dated from the fifteenth century, while the north transept, probably part of an earlier cruciform building, had been erected two hundred years before that. When plaster ceilings were removed, the timbers of the transept roof were found to be sound and would be carefully preserved, as would the old wagon roof of the south aisle. The nave roof, however, was decayed and would be replaced with new oak work, richly carved.

There were monuments inside to the families of Hele, Calmady, and Lockyer, long connected with Wembury’s history. The paper recalled that thirty-five years earlier there had been traces of ancient screens and carved bench ends, now gone, but the restoration would include new oak work “of the same type and character” so that the church would once more be worthy of its heritage.

Much of the labour was being done by Mr Cory’s own workmen, with the artistic carving and detail entrusted to well-known firms under the direction of the architects Messrs Hine and Odgers of Plymouth. It was expected that the church would be securely roofed before the coming winter and reopened by the Bishop of Exeter the following summer.

The article ended by reminding readers that Wembury’s history stretched deep into the Middle Ages and beyond. Among its most notable natives, it said, was Walter Britte, the follower of John Wycliffe, mathematician, and early writer on astronomy and theology, who was believed to have been born at Wembury. The manor, it concluded, had long been held by a family of the same name.

(Source: Western Morning News, 12 August 1885 — “Wembury and Its Church.”)

Entries are summaries and interpretations of historical newspaper reports.